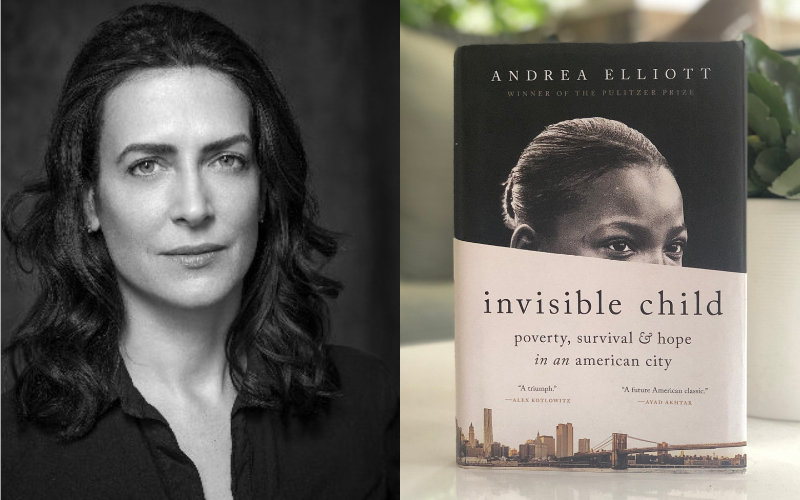

Andrea Elliott

Invisible Child: Poverty, Survival, and Hope in an American City

Random House, October 2021

624 pages

New York Times reporter Andrea Elliott has written a book that will remain with you long after you turn the last page. Based on eight years of embedded reporting, Invisible Child tells the story of Dasani, one of 22,000 children living without housing in New York City in 2012, her seven siblings, her parents Chanel and Supreme, the historical forces that shaped their family over generations, and the institutions that dominate their lives. As children, Chanel and Supreme experienced homelessness, addiction, violence, and trauma. As adults, they are in and out of drug treatment programs and the justice system and cannot hold down a job. When Elliott meets the family, they are sleeping ten to a room in a shelter infested with mice, roaches, mold, and lead paint that generates 350 calls to 911 in a single year.

Elliott follows Dasani from the age of 11 to 18 as her family moves around the city and through the public welfare, housing, and child protection systems. She observes the parental failings that force the siblings to parent one another, warming bottles, scrubbing floors, and creating schedules to structure their lives. She recognizes that “to be poor is to be stressed,” which impedes problem solving and impulse control. And she illuminates the deeper failures of a system that refuses to transfer food stamps from one parent to another, ignores multiple complaints about dire housing conditions, and then spends $400,000 a year to keep Dasani and her siblings in foster care after removing them for neglect.

“When families of means are in crisis,” Elliott writes, “friends and relatives tend to offer material help. They drop off casseroles or make phone calls to doctors. They see their primary purpose as one of stress reduction, because no family can properly function…when the electricity has been cut or the fridge is empty.” In contrast, when poor families are in crisis, what the child protection system often offers is therapy or parenting classes. This approach, Elliott says, quoting the scholar Dorothy Roberts, “hides the systemic reasons for poor families’ hardships by primarily attributing them to parental deficits and pathologies that require therapeutic remedies rather than social change.”

Frontline workers, like the dedicated principal of Dasani’s middle school, Paula Holmes, recognize the futility of this approach: “For a child to truly thrive, says Holmes, her parents would be more than monitored. They would be given material help to fight housing instability, unemployment, food scarcity, segregated schools, and other afflictions common to the poor. Rarely does this happen. A child like Dasani is either surveilled by ACS [the Administration for Children’s Services] and stays with her family, or she lands in the thicket of foster care.”

The threat of removal looms particularly large for Black families, as Elliott notes: “This year [2015] alone, ACS will remove 3,232 children from their parents, more than 94 percent of whom are Black, Hispanic, Asian, or ‘other.’ This is not unique to New York. Over half of all Black children in America are subjected to at least one child protection probe before turning eighteen. They are 2.4 times more likely than whites to be permanently separated from their parents, entering a foster care population of more than 427,00 children nationally. So prevalent is the view that Black parents are being criminalized—many of them mothers like Chanel—that advocates have nicknamed this practice Jane Crow.”

It is impossible to read Invisible Child without feeling deep anger and frustration at the institutions and individuals who fail Dasani and her siblings–and thousands of children like them–again and again. But Elliott’s book, which received the 2022 Pulitzer Prize for general nonfiction, is more than an indictment of systems or people. It is also the story of the fierce love that ties Dasani to her family–and the indelible portrait of a bright, passionate child, trying to figure out who she is as she becomes a young woman, living in extreme poverty in one of the greatest cities in the world.

-Review by Mary Kwak